2858-DEV-SOF.BG-2017

Client: Unknown

Status: Academic

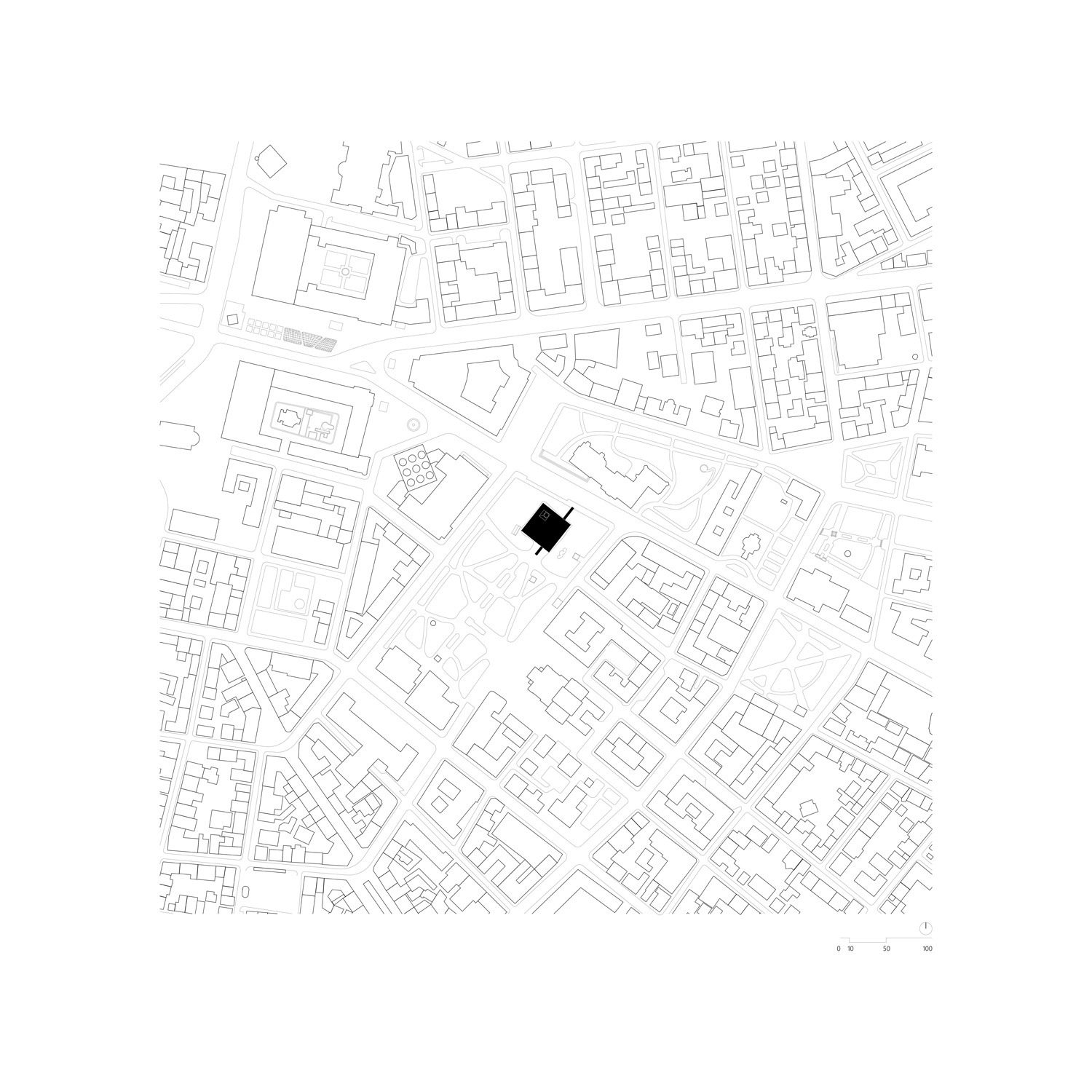

Location: Sofia, Bulgaria

Coordinates: 42.6959165, 23.3263662

Climate: Humid subtropical, Temperate

Material: Metal

Environments: Urban, Park

Visualizer: Studio

Budget: 7.000.000 €

Scale: 7.000 ㎡ Medium

Ratio: 1.000,00 €/㎡

Types: Cultural, Cultural center

The destructive character sees no image hovering before him. He has few needs, and the least of them is to know what will replace what has been destroyed. First of all, for a moment at least, empty space – the place where thing stood or the victim lived. Someone is sure to be found who needs this space without occupying it. – Walter Benjamin

The destructive character, just as described by Walter Benjamin in his essay of the same name, has been actively at work at the Battenberg square in Sofia, Bulgaria for the past three centuries. The first building known to have been on this site is the Konak from 18th century, which existed up until 1880 and served as a representation of the Ottoman rule in the town. Soon after the liberation from the Ottoman Empire the Bulgarian Knyaz (Prince) Alexander I Battenberg assigned the Viennese Architect Viktor Rumpelmayer to design a palace on the foundations of the Konak. This act aimed to eradicate the residual signs of the Ottoman repression and to serve as a symbol of the newly liberated and European-oriented Bulgarian Kingdom.

However, when the monarchy was officially abolished on 15th September 1946 and the People’s Republic of Bulgaria began its existence, this same palace was now considered a symbol of the ‘bad’ tsarist rule. On 2 nd July 1949 Georgi Dimitrov, who was the founder of the Bulgarian Communist Party, died in Moscow. On the next day the demolition of the palace’s gardens began and on 10th of July, just 8 days after his death, a Mausoleum for his embalmed body was built on the same place. The Mausoleum stood as a bold juxtaposition to the Palace as it consciously avoided any coherence with its urban raster and simultaneously aligned with the new ensemble of communist buildings.

The lifespan of these politically charged symbolic edifices became shorter and shorter with the Mausoleum existing for only 50 years; from 10th July 1949 to 27th August 1999. The young and hesitant democracy needed a stable new ground from which it could thrive. The removal of the communist symbol was seen as a necessity, however, this time there was no clear idea what had to substitute it; just the pure and youthful need to “make room”. Up until today the site is an empty urban void, a liberating starting ground for something new.

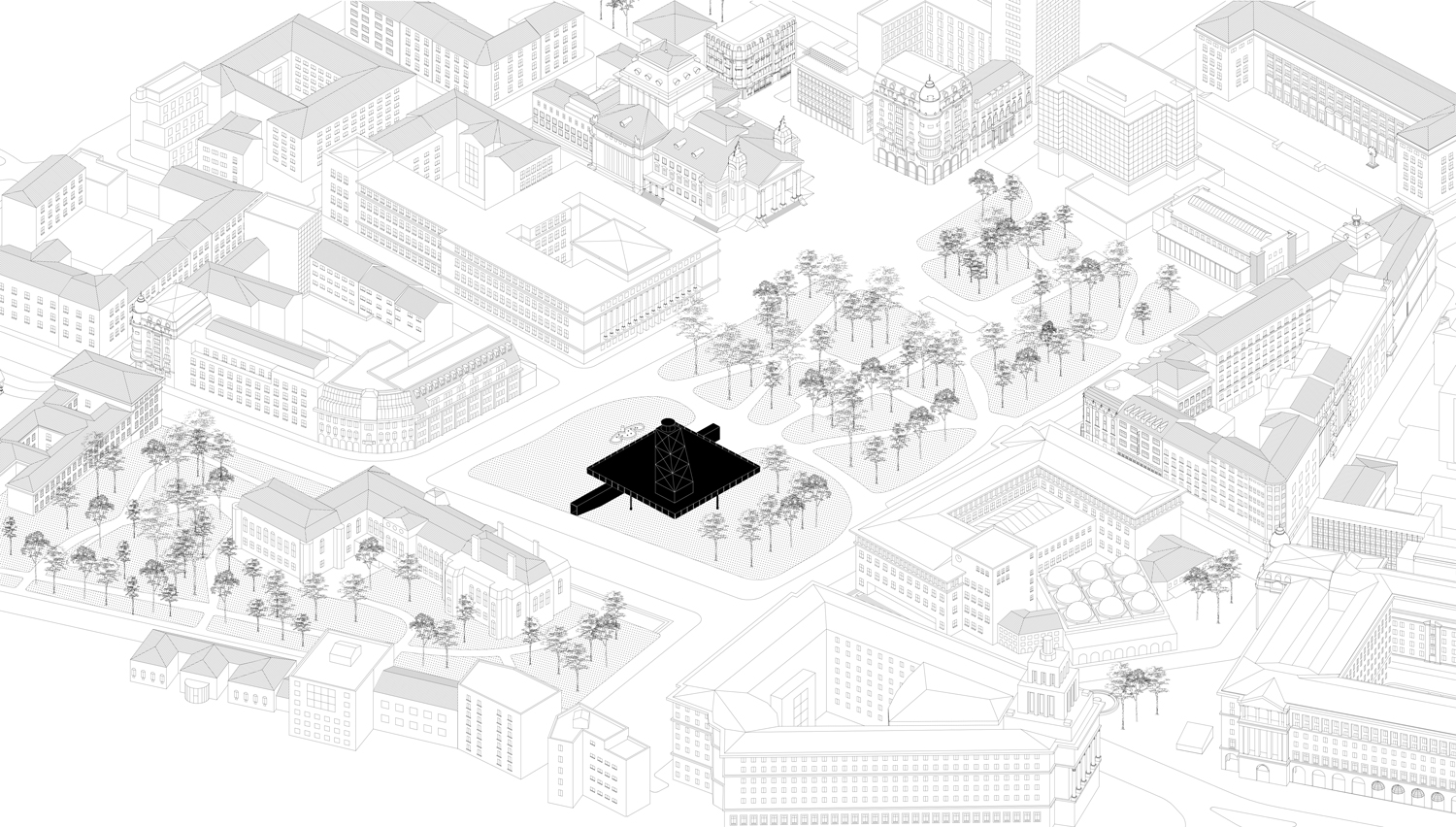

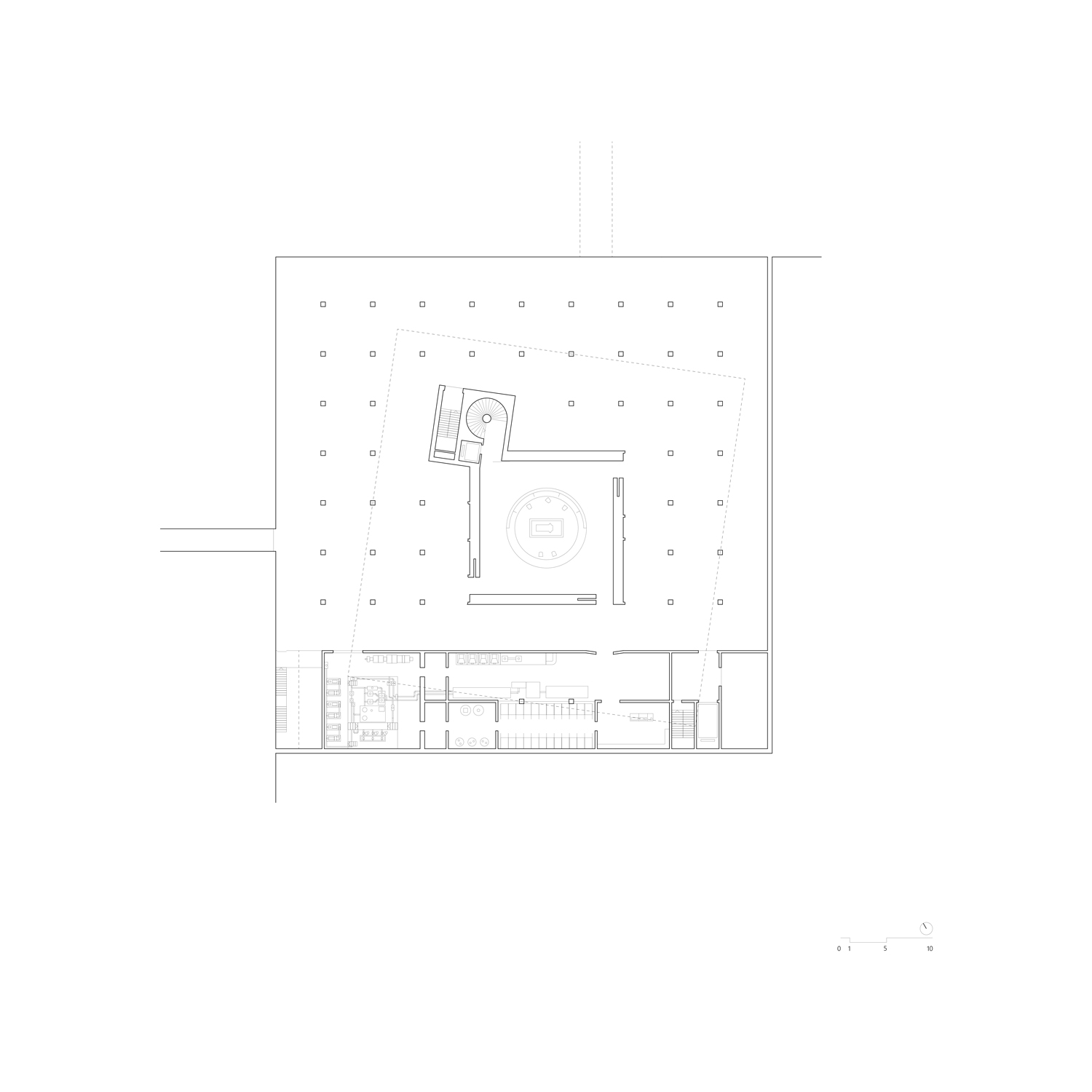

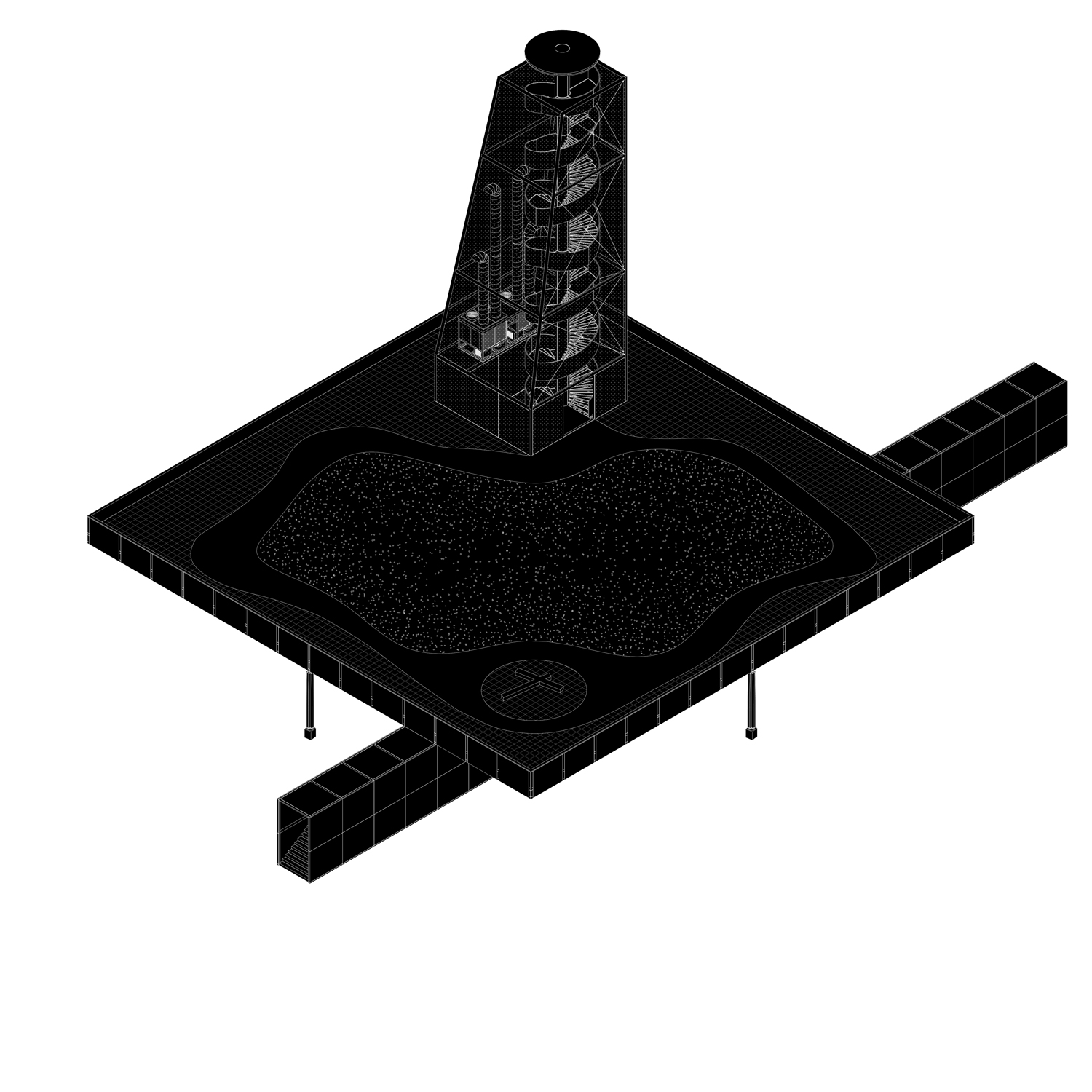

If taken out of context, one might easily misinterpret Benjamin’s writing as a manifesto to nihilism or destructive anarchism. Nonetheless, the destructive character is described as an impulse to create and to see things not as “untouchable objects” that demand to be preserved “as is”, but rather as “situations” or opportunities to create something new. In this line of thought, the remaining underground floors of the Mausoleum are seen as a “situation” in need of a reinterpretation by the means of a gentle and meaningful destruction, rather than simple conservation. Just as the demolished overground part of the Mausoleum, they follow the urban grid of the communistic Largo.

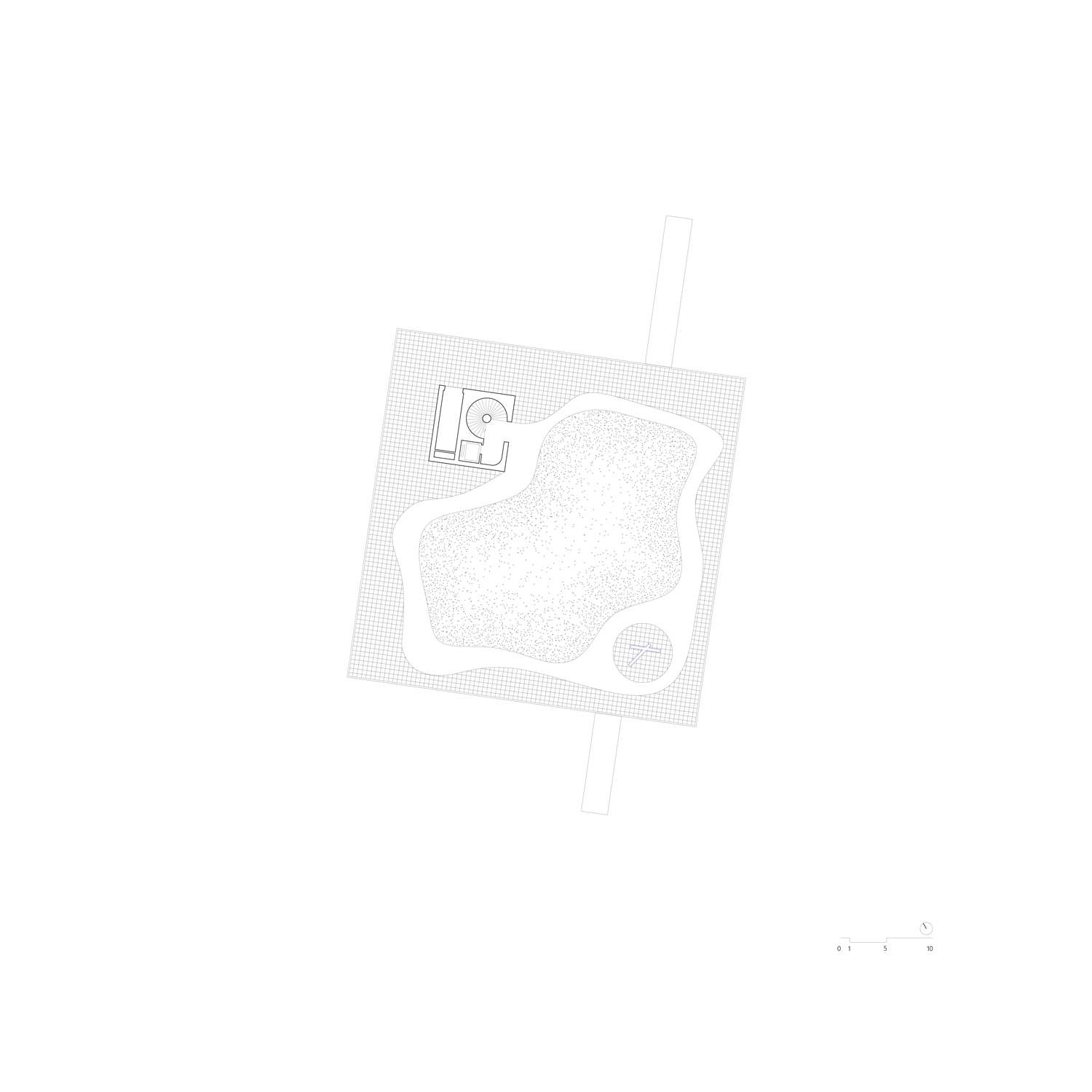

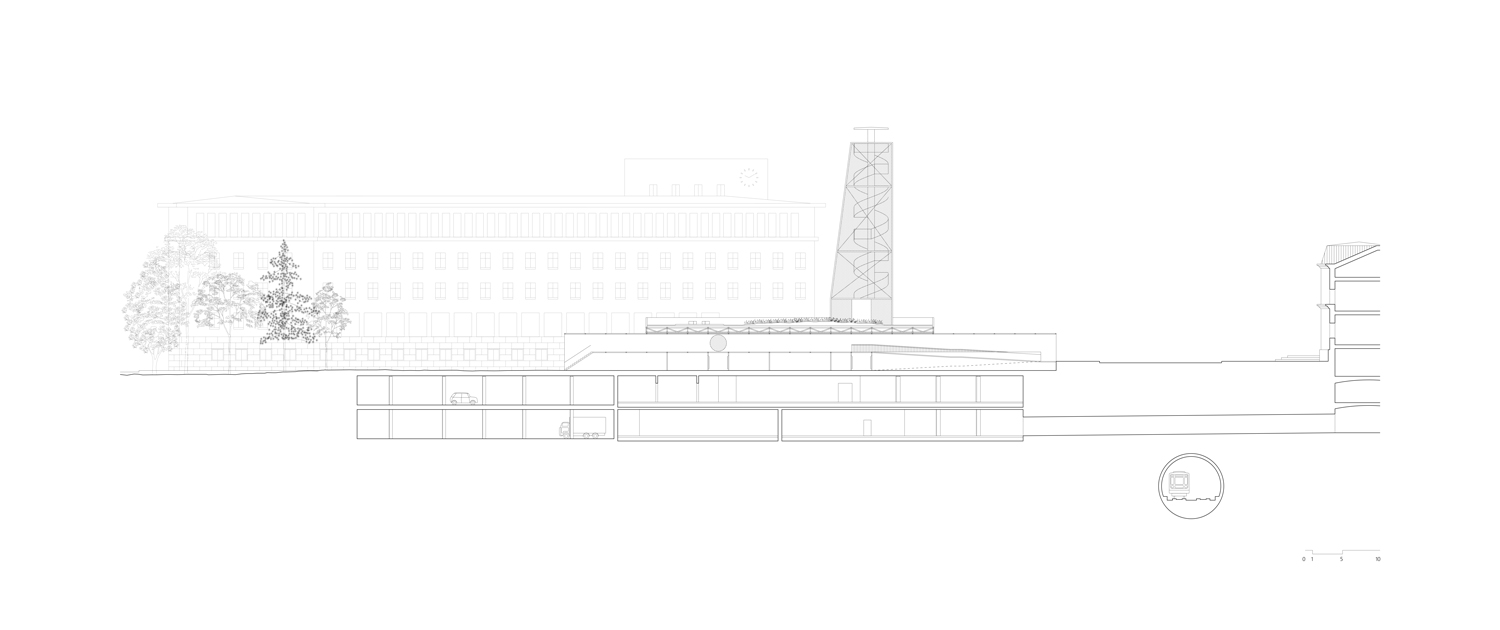

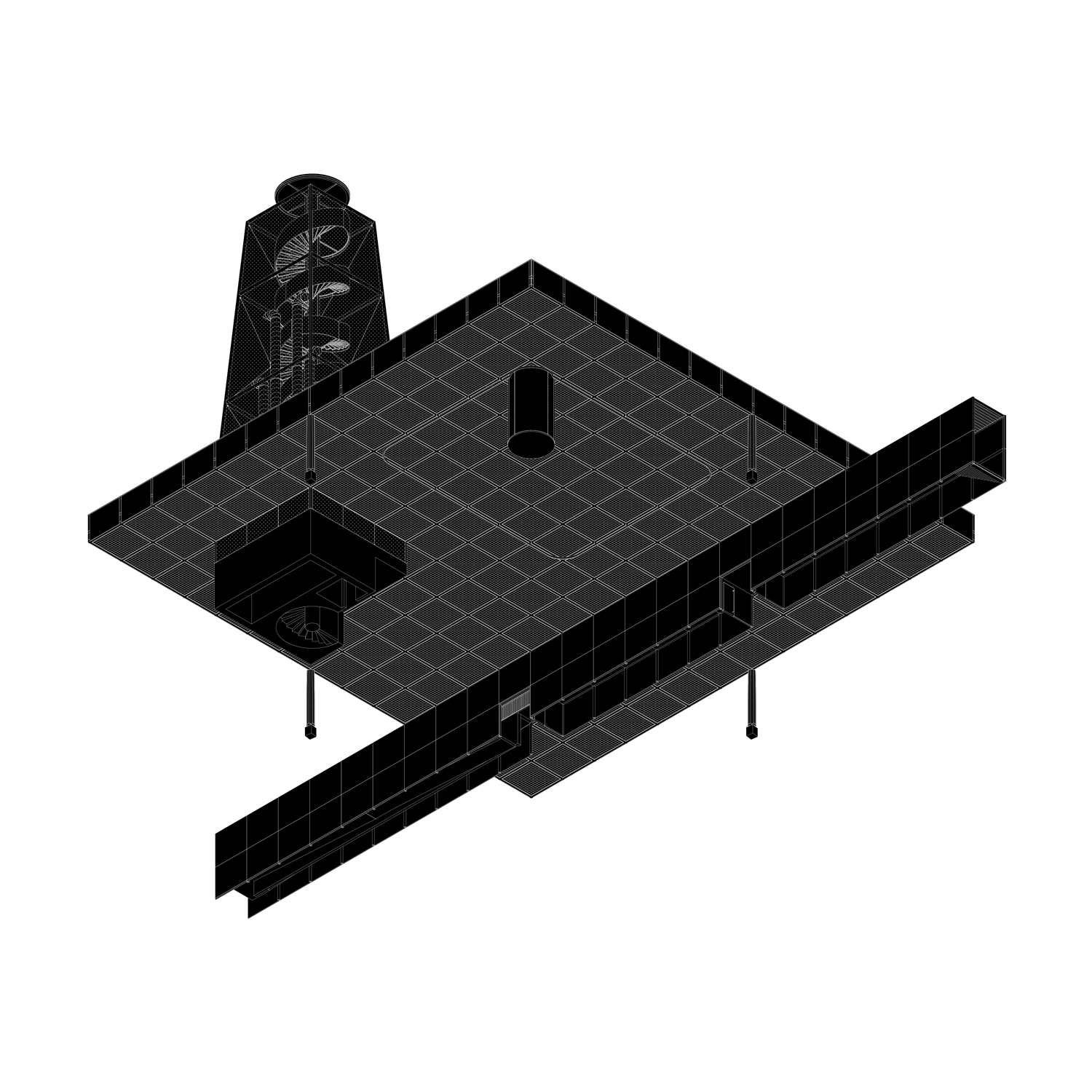

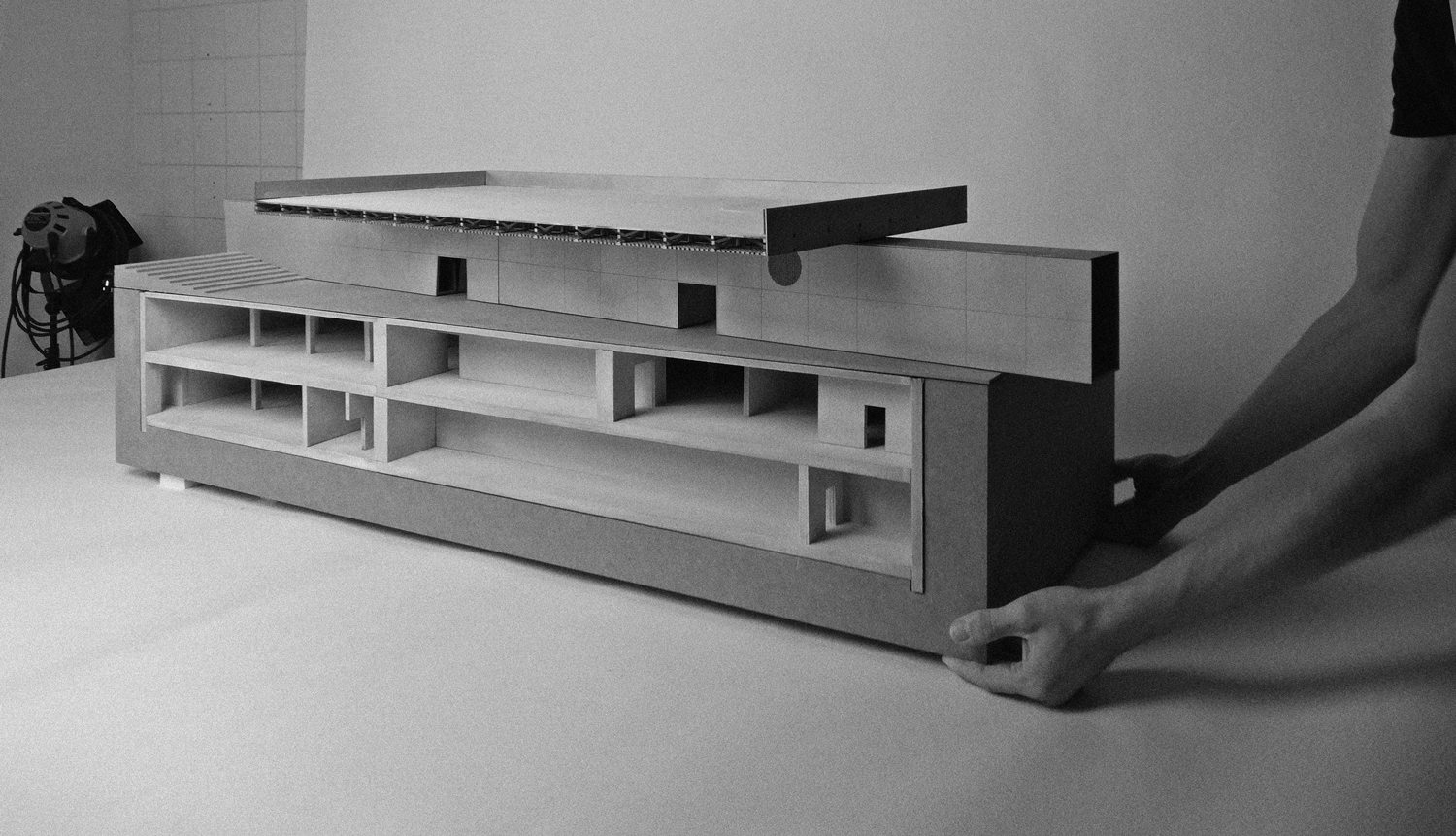

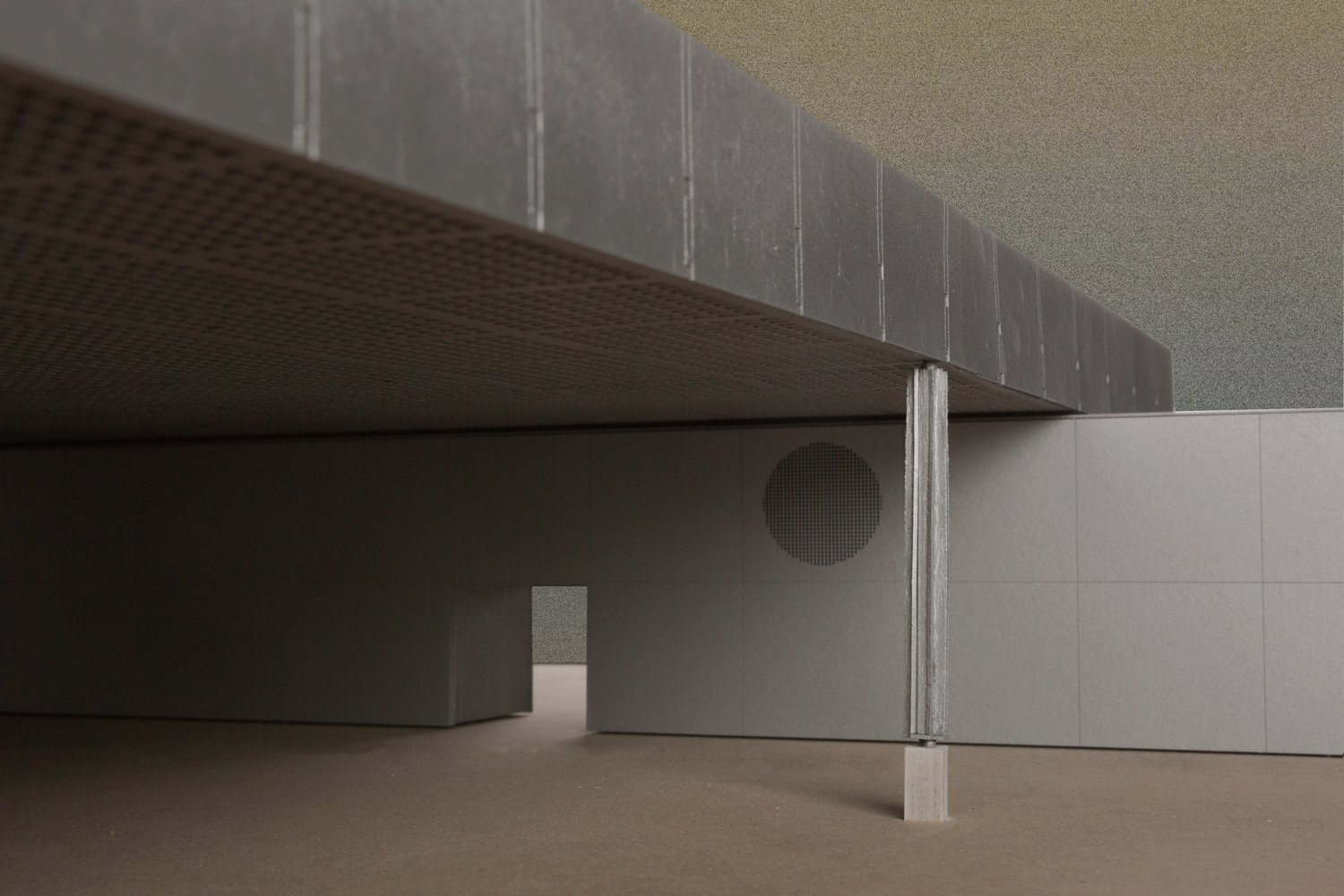

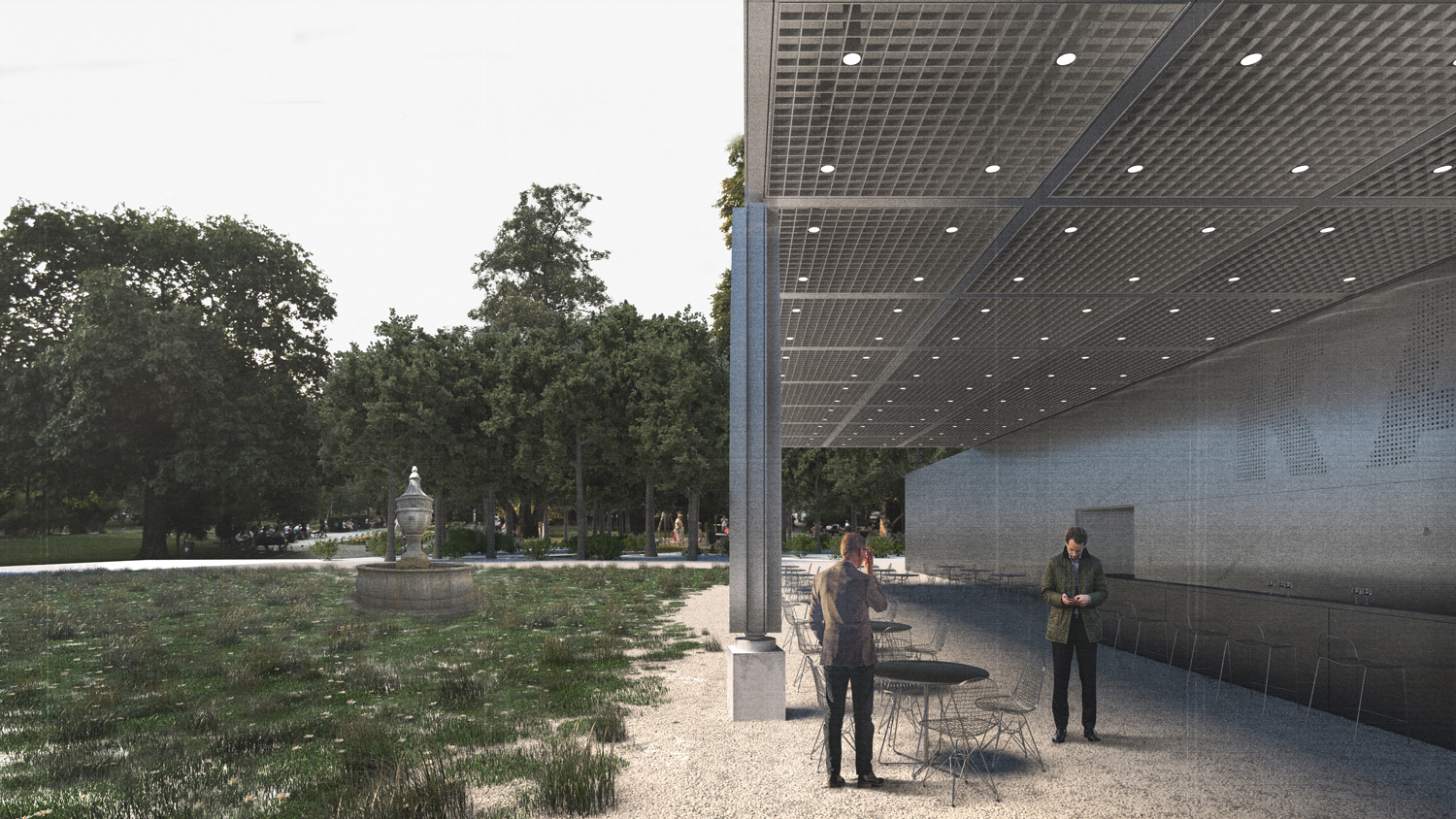

The technical rooms with the unique machinery are going to be preserved and extended to offer new exhibition spaces to the National Gallery, which is currently housed in the Tsar’s Palace across the street. To fill the vacuum created by the demolition, a new overground structure is proposed in the form of an extensive collective roof of an anonymous square shape that follows the grid of the palace and the park it belongs to. It offers a semi protected space of vague programmatic functions underneath it- a place for open discussions, a sculpture garden, a shaded place to relax in a hot summer day, a space for small open-door concerts, separated from the park just by a metallic curtain.

Both systems meet and merge on four points. The enormous tension created by the superimposition of these two politically justified urban systems is condensed to the extreme in just one architectural element, the column, which sits on those four distinct points. The concrete construction of the underground floors effortlessly transforms into the purely metal assembly of the overground structure.