Proyecto: Extension of the Dutch Parliament

Arquitecto: OMA

Equipo concurso: Rem Koolhaas, Zaha Hadid, Elia Zenghelis, Richard Perlemutter, Ron Steiner, Elias Veneris

Situación: La Haya, Países Bajos

Estado: Concurso

Fecha concurso: 1978

Cliente: Dutch Government

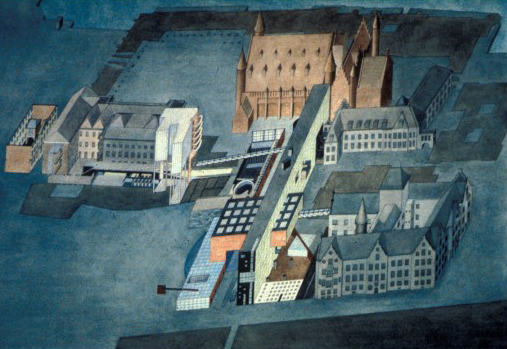

Desde el siglo 13, el complejo Binnenhof ha experimentado un continuo proceso de transformación, tanto arquitectónico y programático en el que sus formas defensivas fueron sustituidas por funciones representativas y simbólicas. A través de los siglos ha servido como un palacio real, archivo, sede republicana, y luego palacio real otra vez, hasta que fue completamente «conquistado» en el siglo 19, en un principio por los diversos ministerios y, finalmente, por el parlamento. Con el fin de adaptarse a estos cambios en la función, todos los estilos arquitectónicos desde la Edad Media hizo contribuciones significativas y tangibles para el complejo que lleva a cambios graduales en las paredes de la fortaleza, en el que las paredes se han convertido en un conglomerado de diferentes estilos históricos.

Superponer a estos cambios auténticos en una capa de restauraciones destinadas a preservar la historicidad del complejo sólo demuestra que cada acto de conservación representa una revisión, una distorsión, y un nuevo diseño. El mayor bloque único de la historia fabricada es ahora el Ridderzaal, cuyo gótico autentico ha sido reemplazado por un restaurador del siglo 19 en una fantasía de la Viollet-le-Duc.

En 1978 se celebró un concurso para corregir esta ambigüedad. A este área vagamente triangular del Binnenhof fue designado como el sitio para una muy necesaria ampliación de la vivienda parlamentaria. Esta extensión también para proporcionar una restauración del simbolismo, para separar conceptualmente el gobierno y los representantes que se supone que deben supervisar sus acciones.

En la propuesta de OMA, el Binnenhof todo se ve como sometidos a un proceso lento de transformación, en el que las instituciones democráticas invaden y se apropian de la tipología de la fortaleza feudal. Sólo una arquitectura que no se disculpa por su modernidad puede preservar y articular esta tradición. En esta interpretación, toda la doctrina historicista representa, de hecho, las interrupciones o las obstrucciones de esta transformación.

De acuerdo con esta lectura, la «conquista» de la Binnenhof se convierte en definitiva, con la introducción del nuevo parlamento. Se ha concebido como la representación arquitectónica de la ofensiva final que crea una brecha de la modernidad en las paredes de la propia fortaleza.

El programa total del concurso – para todas las instalaciones parlamentarias – debía ser dividido entre un número de estructuras existentes que se tenían que conservar, y un nuevo edificio(s) que han de representar a la autonomía del Parlamento.

En el esquema de OMA, la tradición en la que cada edad se manifiesta dentro de las paredes de la Binnenhof se mantiene a través del transplante de una estructura del siglo 17 a una posición frente al complejo, donde en parte se deshace la Corte de Berlage de tráfico y restaura parte de la definición original de la Buytenhoff. La brecha abierta por esta eliminación es ocupada por los dos bloques: uno horizontal, la vertical.

La losa horizontal – un podio de ladrillo de vidrio – contiene el centro de todo el proyecto. Se concibe como un podio cubierto por la actividad política, directamente accesibles al público en general de la plaza contigua. La losa vertical contiene adaptaciones de los políticos profesionales.

Las 340 habitaciones para los miembros del parlamento y sus asistentes se alojan en las estructuras existentes a lo largo del Binnenhof, tres de los cinco patios han sido conectados para formar una galería que dirige todo el tráfico hacia una rampa de división y, a su vez conduce directamente al ambulatorio y al sótano de la sala de conferencias.

En un proyecto donde se distribuyen un gran número de elementos de programa, la calidad de las conexiones determina la calidad del proyecto.

Esquema de OMA se basa en dos ejes cruzados – una es la arcada nueva que corre de norte a sur a través de los edificios existentes, y el otro es el ambulatorio, que corre de este a oeste a través del centro de la losa.

Desde la entrada, un sistema de escaleras mecánicas conduce directamente a la galería del público del salón de actos, un rectángulo que rodea completamente a los parlamentarios. Todo el entresuelo contiene instalaciones para la prensa: un haz lineal de las redacciones y una plaza de prensa para más actos públicos como conferencias. La planta baja, básicamente sirve como un hall de entrada, los segmentos son examinados fuera de las reuniones informales. La estructura oval alberga tres salas de conferencias unidas por una rampa en espiral.

Since in the 13th century, the Binnenhof complex has undergone a continuous process of both architectural and programmatic transformation in which its defensive forms were replaced by representative and symbolic functions. Over the centuries it has acted as a royal palace, archives, Republican headquarters, and then royal palace again, until it was completely ‘conquered’ in the 19th century, initially by various ministries and eventually by the parliament. In order to accommodate these changes in function, all architectural styles since the Middle Ages made significant and tangible contributions to the complex leading to incremental changes in the walls of the fortress, whereby the walls have become an agglomeration of different historical styles.

Superimposed on these authentic changes is a layer of restorations intended to preserve the complex’s historicity, but which only proves that each act of preservation embodies a revision, a distortion, even a redesign. The largest single block of fabricated history is now the Ridderzaal, whose Gothic authenticity has been replaced by a 19th century restorative fantasy à la Viollet-le-Duc. There is very little medieval medieval architecture left; the Binnenhof has become a catalogue of medievalness.

In 1978 a competition was held to correct this ambiguity. A vaguely triangular area east of the Binnenhof was designated as the site for a much-needed extension of the parliamentary accommodation. This extension also had to provide a restoration of symbolism, to separate conceptually government and the representatives who are supposed to supervise its actions.

In OMA’s proposal, the entire Binnenhof is seen as undergoing a permanent, slow-motion process of transformation, in which democratic institutions invade and appropriate the feudal typology of the Fortress. Only an architecture which is unapologetic about its modernity can preserve and articulate this tradition. In such an interpretation, all historicist doctrine represents, in fact, interruptions or even obstructions of this transformation.

According to this reading, the ‘conquest’ of the Binnenhof becomes final with the introduction of the new parliament itself: it is designed as the architectural representation of the final push which creates a breach of modernity in the walls of the Fortress itself.

The total program of the competition – for all the parliamentary facilities – was to be divided between a number of existing structures which had to be preserved on the one hand, and the new building(s) which had to represent the autonomy of the parliament on the other.

In OMA’s scheme, the tradition where each age manifests itself inside the walls of the Binnenhof is maintained through the transplantation of one 17th century structure to a position in front of the complex, where it partly undoes Berlage’s traffic cut and restores some of the original definition of the Buitenhof. The breach created by this removal is then occupied by two slabs: one horizontal, the other vertical.

The horizontal slab – a podium made of glass brick – contains the entire conference center. It is conceived as a covered podium for political activity, directly accessible to the general public from the adjoining plaza. The vertical slab contains accommodations for professional politicians. An ambulatory runs horizontally through the assembly, towards the ‘smoke-filled room’. Above the ambulatory are three floors where the thirteen political parties prepare their positions; from there they then filter down to the ambulatory and the assembly. Below the ambulatory are three floors for the managers of the parliamentary procedures.

The 340 rooms for the members of parliament and their assistants are accommodated in the existing structures along the Binnenhof; three of the five courtyards have been connected to form an arcade which directs all traffic towards a split ramp, and in turn leads directly to the ambulatory and to the basement of the conference hall.

In a project where a large number of programmatic elements are distributed over both new and existing structures and scattered over a vast site, the quality of the connections determines the quality of the project.

OMA’s scheme is based on two intersecting axes – one is the new arcade that runs north-south through the existing buildings; the other is the ambulatory, running east-west through the middle of the slab.

From the entrance, a system of escalators leads directly to the public gallery of the assembly hall, a rectangle that completely surrounds the parliamentarians. The entire mezzanine level contains facilities for the press: a linear beam of editorial offices and a suspended press plaza for more public events such as press conferences. On the ground floor, which basically serves as a lobby, segments are screened off for informal meetings. The oval structure contains three superimposed conference rooms connected by a spiraling ramp. The ground floor area also contains the reception and stage accommodation for the Department of Petitions (to the left); petitions are displayed in steel storage cabinets as tangible evidence of the volume of public participation in the parliamentary process.