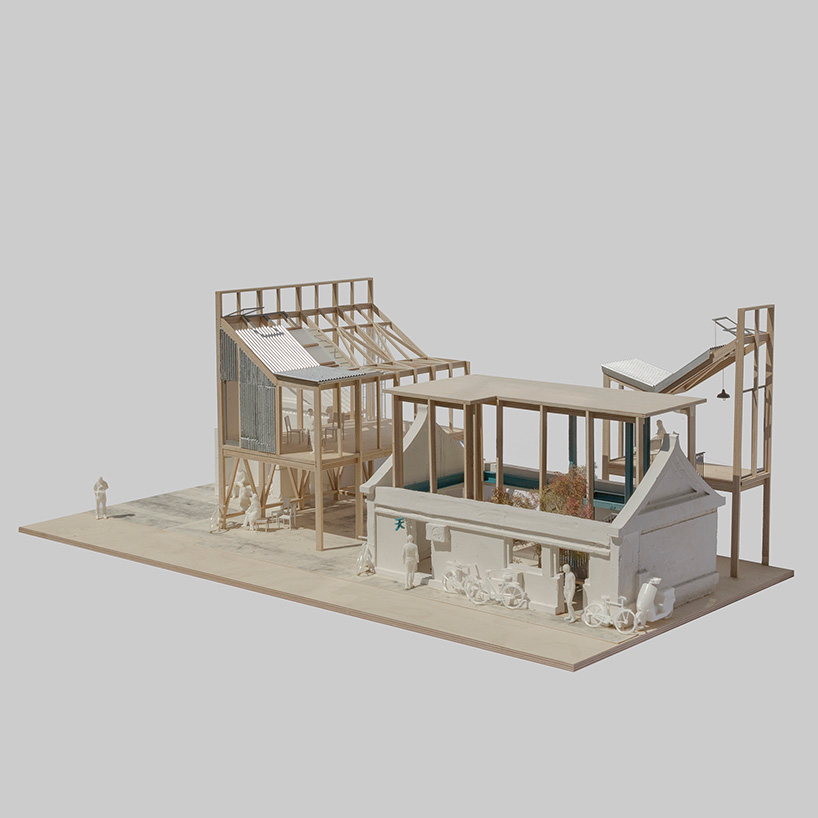

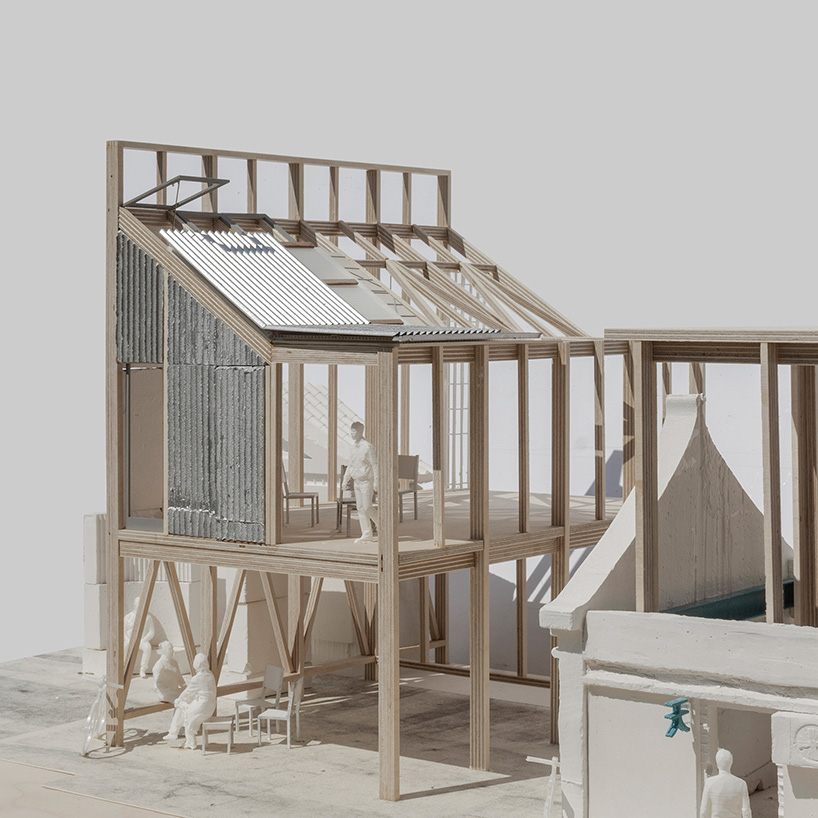

☉ Close to Home is a proposal by Cameron Clark developed. It is located in Beijing China in an urban setting. Its scale is small with a surface of 600 sqm. Key material is wood.

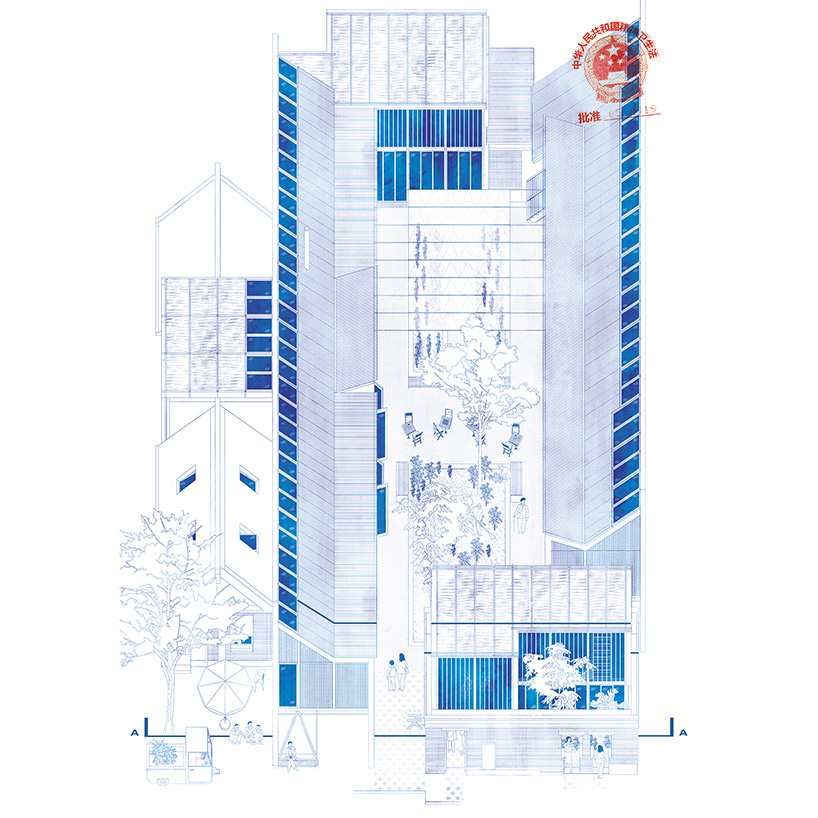

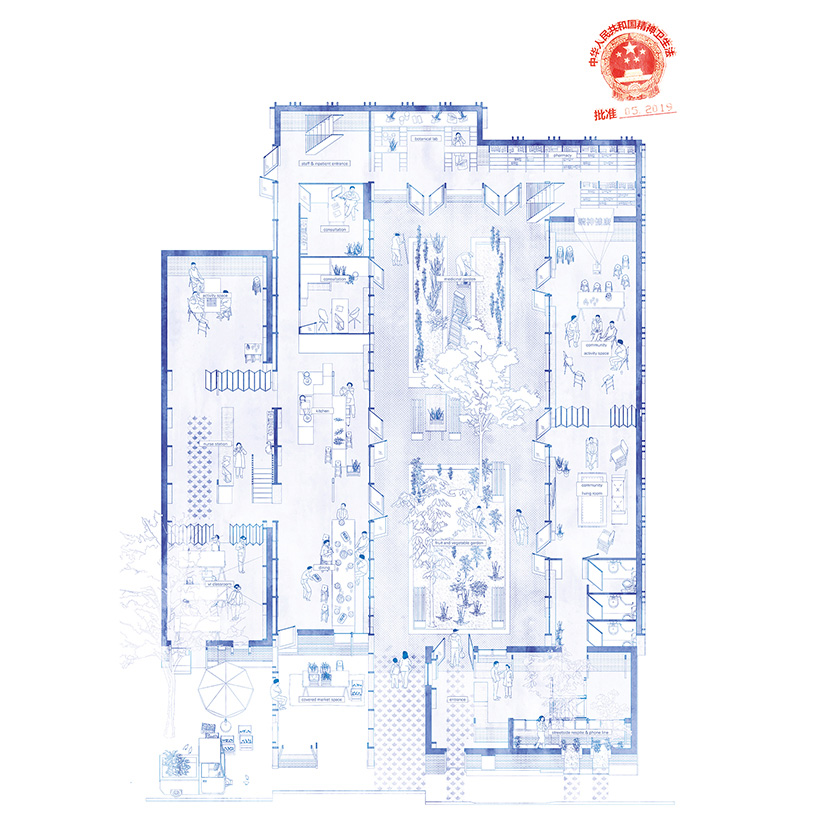

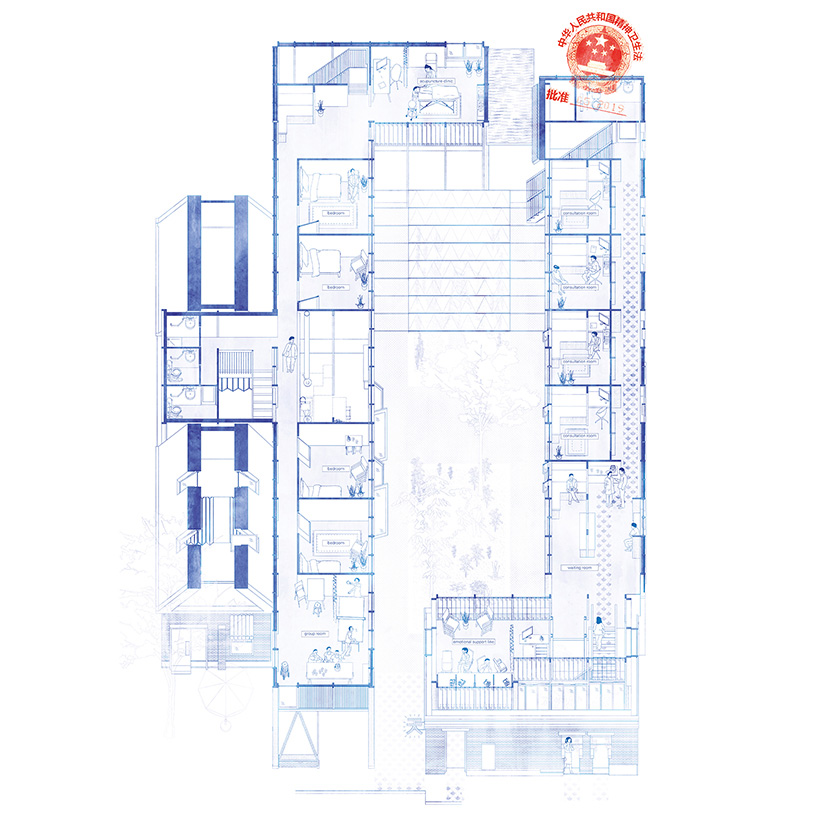

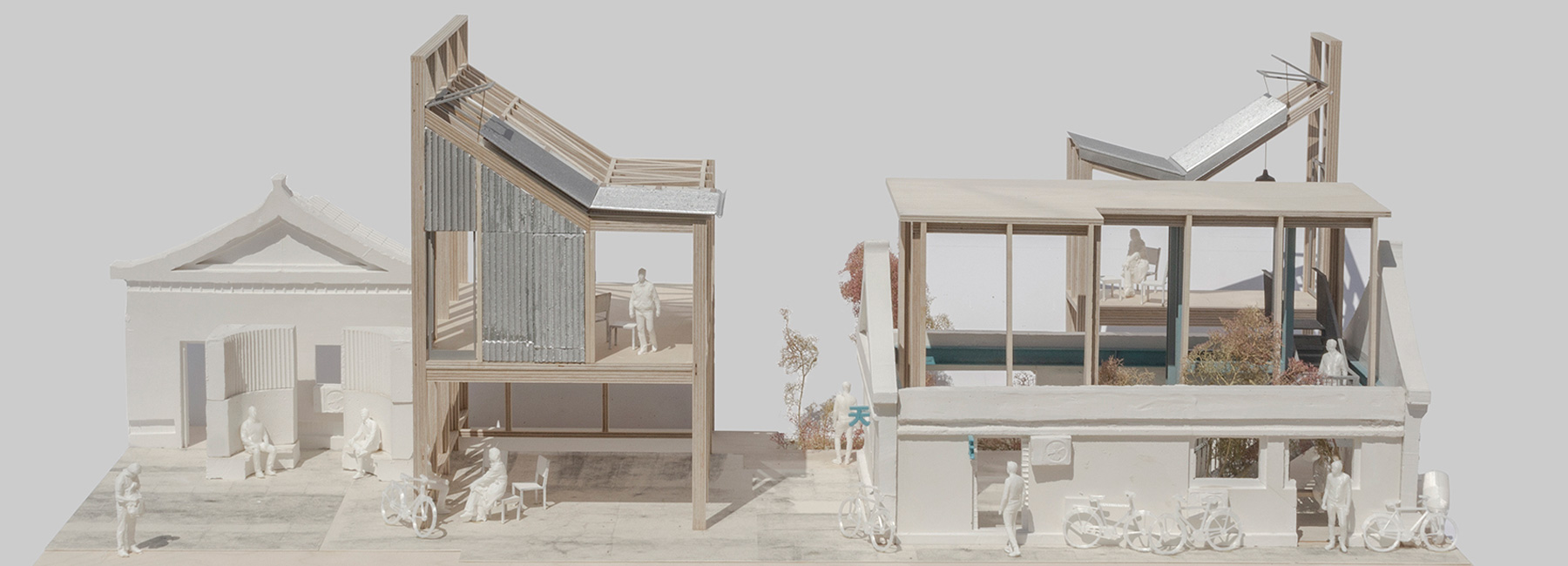

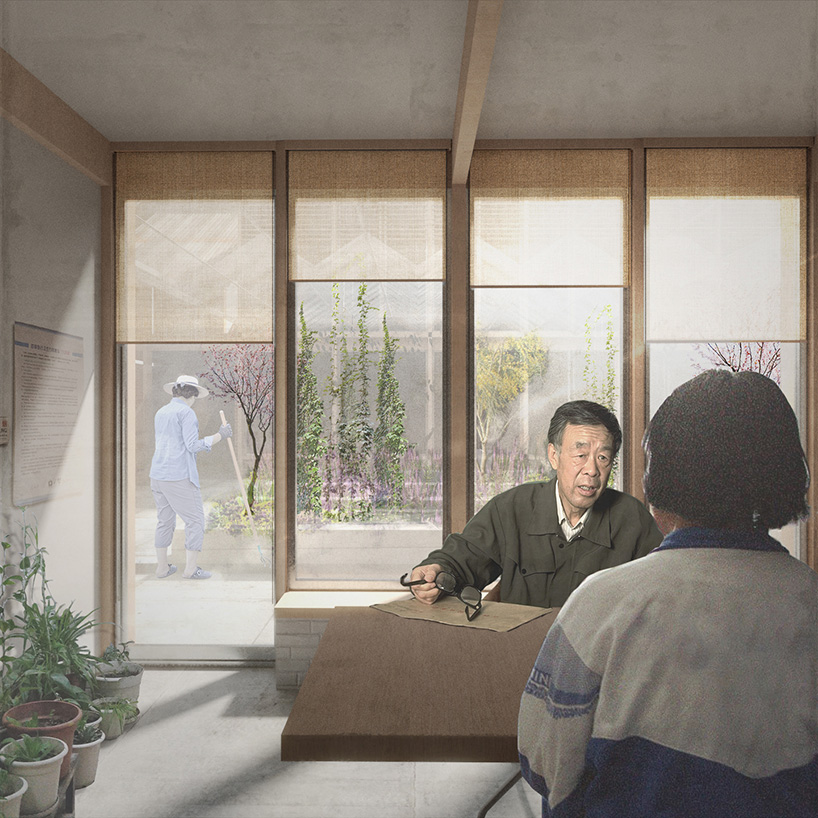

‘Close to Home’ is a speculative architectural and research project which engages in one of the key challenges of today’s rapidly urbanising world – mental health. Often stigmatised and misinterpreted, mental healthcare facilities in China are typically large, centralised and inhumane institutions located far from the everyday spaces of their users. Based on a process of interdisciplinary research and design speculation, this project posits a local alternative in the urban setting of Beijing, where mental health care is of immense urgency. Each intervention is crafted and represented with precision through a range of architectural media, including drawings, models, animations and a design manual which speculates on potential architectural interventions made across the city fabric. In strengthening existing communities and neighbourhood structures, the project explores how architecture could play an essential role in ensuring the future mental well-being of our urban lives.

In the last 30 years China has developed economically, socially and urbanistically at an unprecedented rate. Following the opening up of the country to the market economy at the end of the 1970s, China’s towns and cities have grown beyond previous comprehension, and many of their citizens have relocated from the countryside in search of the vast array of opportunities that urbanised China can offer.

This has placed enormous strain on the built environment, its infrastructure and has caused wide-scale pollution. In the last 10 years there has been much debate over how the Chinese government can mitigate these decremental phenomena. These changes have also caused increased strain on Chinese citizen’s mental health, as the pressures and stresses of rapid change impacts upon all aspects of urban life. This has been relatively little discussed, and leaves the country ill prepared to face the scale of the mental health crisis which is upon it.

Mental illness is now the leading cause of health burden in the country , and it is already costing China many lives, and billions of dollars. In order to adequately deal with the scale of the crisis, China must look towards systemic change rather than piecemeal improvements. But the country has shown, perhaps beyond all others in modern history, a remarkable capacity for large scale change over short periods of time. In the last 30 years, China has transformed a largely rural society into a rapidly urbanised one, now with six times as much urban area than in 1981 – an urbanisation which has caused significant strains on its citizens, but also created enormous creative capacity for change, as a result of which the Chinese “tech revolution is now ubiquitous in urban life.” Although slow to develop policy, the Chinese government has stated its commitment to prioritising finding new ways to treat mental health illness. But, as we find in Europe and the US, it will often be the tech innovators and creators who change modes of treatment before official policy catches up.

This is a process architects and urbanists must engage with, as their contribution in designing spaces for care will be as vital as ever, even though the physical realities will be mediated increasingly through wider systemic technological, digital and virtual infrastructures. As urban life in China becomes increasingly digitised; and social relations move between offline and online, social services (such as mental healthcare) should be “seen as networks rather than as bounded and closed spatial units.” (Curtis, 2009. p.341).

There is an exciting opportunity for China to develop a new network which delivers mental healthcare through a holistic range of novel mediums, from VR to social networks, while retaining much that is effective and necessary in traditional Chinese urban culture. In this network the spaces that architects and urbanists create “should be seen as nodes in the network, or field, influencing and being influenced by other nodes” where increasingly “one cannot make a clear distinction between what is occurring ‘outside’ or ‘inside’ a place.” (ibid).

In previous research I developed an understanding of the traditional Beijing Hutong neighbourhoods through the lens of my project ‘HomeMaking’, the process by which local communities were responsively adapting to meet the growing demands upon them by urban, economical and technological development. I discovered an incredible resilience and adaptability to this rapid change, and that its potential for success was based on its traditionally strong network of social connections and uptake of emerging digital communication platforms. This web of interconnection enabled incredible nimbleness of social and economic productivity.

I intend to use this project to investigate if the same neighbourhood resilience could be meaningfully applied in an exploratory approach to tackling China’s impending mental health care crisis. The project offers some propositions about how these strategies can be manifest in the built environment, imagining how a networked approach to healthcare, which combines existing social resourcefulness, emerging digital technologies and contextual architectural intervention. ‘’Close to Home’’ develops a design strategy at the scale of the neighbourhood, which takes the opportunities that are presented by emerging technologies such as virtual reality and the traditional scales of architectural & urban intervention.

These scales of proposal are woven together through a re-purposing and re-imagining of latent community & urban networks and structures, to form a proposal for an adaptive, responsive, scalable and contextual neighbourhood mental healthcare strategy. It imagines a Community Mental Health System based upon the recovery approach which resonates strongly with traditional Chinese culture and is consistent with the government’s 686 Project, paying more attention to the patient’s level of functioning and their strengths, rather than their disabilities and psychopathology. The recovery approach emphasises self-confidence ⾃信, self-help ⾃助 & self-sufficiency ⾃給⾃⾜.The programme will address the treatment gap found between diagnosis and hospital inpatient acute care or medication and will open up awareness of mental illness and wellness for those undiagnosed in the community.